Ch, ch, changes

Thoughts on John, Elijah, and the season of Lent

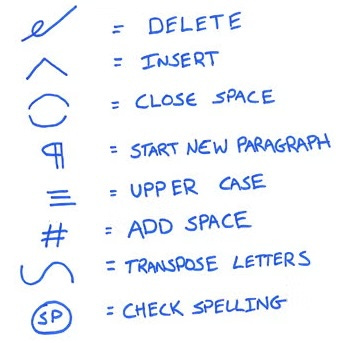

Every time I submit work to my editor, she finds mistakes. Every time. It annoys the living daylights out of me.

“Come on, seriously, can’t you just fix the capitalization yourself?” I mumble to my computer screen. “You could just insert the missing citation or invent a page number I left out? So what if the connection of ideas doesn’t actually make sense? Why are you bothering me with my mistakes?”

Of course, I already know why: It’s my work, not hers. I need to fix it, not her. Plus, there are those pesky copyright laws, so, all right. I take a deep breath, begrudgingly, and fix my mistakes.

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that nobody likes to be held accountable. Or almost no one. There are exceptions.

When John the Baptist arrives on the scene, as an adult, the people seem to want to fix their mistakes and start over. “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near,” he tells them (Mathew 3:2). And fixing our mistakes is what repent means, right: to change, to admit our sins and turn from them, to start over?

Then Jerusalem and all Judea and all the region around the Jordan were going out to him, and they were baptized by him in the River Jordan, confessing their sins. (Matthew 3:5-6)

It’s extraordinary, really, even if there is some scholarly debate about how much Matthew might have exaggerated the numbers. “All Judea and all the region” seems like a wee stretch. Still, it’s a crowd.

Social science predicts a crowd. Social scientists argue that most people like being held accountable. I find this hard to believe, but let’s give them a chance.

“An interesting statistic from the Harvard Business Review helps debunk this idea: 50% of managers avoid holding people accountable, yet 72% of employees say they would benefit from it. So, if people don’t dislike accountability, what’s really going on?” (Read the whole article here.)

Maybe? Maybe we want feedback. Maybe we even accept the punishment. But, do we make the changes needed so we don’t repeat those mistakes? Maybe.

Or, maybe we don’t really want to know when we’ve been wrong. We don’t want to hear that we’ll have to pay a price for our poor judgment. We, as a species, would maybe rather just pretend it didn’t happen.

Later in Matthew’s Gospel, just after the transfiguration, there’s a cryptic little conversation between Jesus and the disciples. It goes like this:

The disciples asked him, “Why then do the teachers of the law say that Elijah must come first?”

Jesus replied, “To be sure, Elijah comes and will restore all things. But I tell you, Elijah has already come, and they did not recognize him, but have done to him everything they wished. In the same way the Son of Man is going to suffer at their hands.” Then the disciples understood that he was talking to them about John the Baptist.

You see, the Jewish people had been told that the prophet Elijah would appear ahead of the coming Messiah. He was their sign of the Savior to come. John was this sign, and the leader and people–all of them–had failed to recognize him when it really mattered. They let him be executed, just as Jesus later would be.

So, did they really change? Did they really turn their lives and the life of their nation around? No.

It’s soon the season of Lent, a season when we’re called to do hard self-examination, to repent, to turn from sin and be made new.

The real proof of repentance, though, isn’t our words, or even our intentions. The real proof of repentance is change, lasting change, and it only comes by faith, courage, and the power of the Holy Spirit.